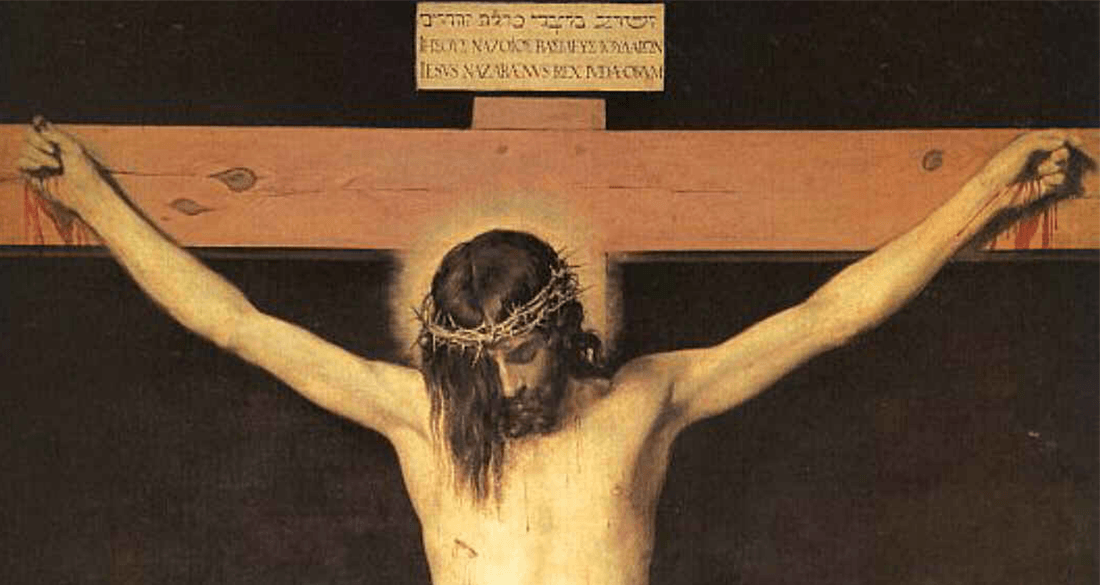

There

was also an inscription over him, “This is the King of the Jews.” (Luke

23:38)

In

my theatre days I had the privilege of working with a talented (if extremely

eccentric!) Brit named David Perry. David was a senior tutor at the Royal

Academy of Dramatic Arts. He drank Shakespeare with his mother’s milk, and I

loved being directed by him in his whimsical but very British way. I think we

worked on about four classical British plays together over the years. Once an

actor asked him why the British would still have the archaic institution of

monarchy in modern times.

“Because,

my dear,”—David called everyone “my dear” regardless of gender—“of the Royal

Prerogative of Mercy. Even if you’re convicted by every court in the realm, you

can still appeal to the Queen for pardon.”

Mercy

and pardon are really the only powers the monarch has left. Britain’s queen and

any king who comes after her won’t be able to raise or lower taxes, decree

laws, send out ambassadors, or declare either war or peace with an enemy. The

monarch is really a symbol of the government. The only power remaining to the

crown is that of royal forgiveness.

And

that’s still a pretty important power to possess.

On

the last Sunday of the liturgical calendar, Christ the King, we behold in our

gospel reading (Luke 23:33-43) another powerless king—Jesus. Declared to be “the

King of the Jews” in an insulting taunt by Pontius Pilate, the condemned Jesus

is nailed to a cross and hoisted aloft to suffer until his lungs fill up and he

drowns in his own bodily fluid. The story in Luke’s gospel is one of complete

and total loss. Jesus’ friends have abandoned him, his body is failing, his

dignity has been stripped away as the crowds and leaders of the people rail and

mock him, and his body is immobilized—he is powerless even to wipe the sweat

from his own eyes.

Yet

he retains the one power of the

monarch—the power to forgive.

As

the nails are going into his hands, so some versions say[i], Jesus proclaims, “Father,

forgive them; they do not know what they are doing.” (v.34) Not even extreme

agony and disgrace can take away the power of compassion and understanding.

The

Prerogative of Mercy is shown again in verse 43 when Jesus comforts the

confessed and condemned criminal at his side, “Truly I tell you, today you will

be with me in Paradise.” The laws of this world may condemn, but they have no

power over the mercy of Almighty God. And this is something we would all do

well to remember. However we may revile those who have trespassed against us,

God has seen to their hearts. God has understood the pain we’ve refused to see

because we are blinded by our love affair with indignation and determined

always to be right.

I

hasten to point out that in the UK the monarch’s power to pardon does not

include the power to acquit. If one is found guilty, the guilty verdict still

stands. It is only the penalty that is lessened. If we are to exercise the

power of pardon which our King has graciously bestowed on us as Christians, we

certainly can’t pretend that a wrong isn’t a wrong or that a hurt isn’t a hurt.

None of us can go back and change the past. But we can examine our own guilty

verdict and the pardon we’ve received and try to apply it to others, always

remembering that what we find impossible to do is still possible for our

merciful King. Perhaps our best response may be to appeal to God to forgive those

things which we cannot forgive ourselves.

May the

spirit of mercy guide us all as we enter into Advent. Thanks for reading my blog this week.

[i] Some

of the earliest known copies of Luke’s gospel do not include this saying. Bible

scholars think it might’ve been inserted later, but I don’t think that matters.

The fact that it became part of the accepted canon indicates that the early

followers of Jesus must’ve preached about the power of forgiveness.

No comments:

Post a Comment