The home my wife and I bought is a modest

one-half of a duplex with two bedrooms and one bath and it’s just big enough

for the two of us and our shih-tzu dog and still comfy if our daughter wants to

come and spend the night. Many of our neighbors, on the other hand, are living

in virtual palaces which range from 1,724 square feet of living space to a

whopping 2,731 square feet. My question is: Why do you need all that room? You

don’t have kids at home anymore, folks! If you’re downsizing in your old age,

just what the heck did you live in before—Windsor Castle..??!

I’ve also noticed that my neighbors have

garages stuffed with so many boxes that they can’t fit their cars in them. “We’ve

been here almost a year,” one of them told me,” and we just haven’t managed to

unpack everything yet.” Now my philosophy is: if you haven’t used it in over a

year, you don’t need it. Give it to someone who does.

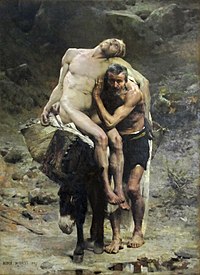

Bigger barns. More stuff. Just like the

guy in the gospel lesson assigned for Pentecost Eleven in the Revised Common

Lectionary (Luke 12: 13-21). He’s got so much more than he will ever live to

need. You have to wonder why he doesn’t solve his storage problem by giving some

of it away. I guess it’s because he feels a need to be in control, and the idea

of praying only for “daily bread” and not for a month’s supply makes him feel

weak and vulnerable. In a 1955 letter to an American friend C.S. Lewis wrote:

“For

it is a dreadful truth that the state of…’having to depend solely on God’ is

what we all dread most. And of course that just shows how very much, how almost

exclusively, we have been depending on things. But trouble goes so far back in

our lives and is now so deeply ingrained, we will not turn to Him as long as He leaves us anything else to turn to.”

(Original emphasis)

The problem is of course, things, barns,

bank accounts, and the like can’t protect us from cancer, heartbreak, or our

own mortality. I don’t have to tell you this. You already know it. I don’t

suppose any of you want your epitaph to read “He/She was the wealthiest person

in town.” You’d much rather have it say “He/She was a good person who loved God

and was loved by all.”

So what does it mean to be rich toward

God? (v. 21) I’d have to say that one is rich towards God if one has an active

life of prayer, a heart full of compassion, a love of the scripture, a passion

for worship, a vast capacity for forgiveness, and a joyful faith in God’s

goodness. And, even though I believe these are gifts of the Holy Spirit, like

any other talents they need to be nurtured and exercised. We need to be

constantly re-investing in our relationship with God. This is a hard habit to get

into—even for me.

Down the street from where I live is the

local mega-church. They’re just finishing building their new worship space. It’s half as big as Rhode Island and I can’t begin to guess how many Christians

will fit inside it. My own little urban Lutheran church is pretty pitiful in

comparison. I’m sure the folks who worship in this big barn are good people who

love God and their neighbor, but I can’t help but wonder what their fellowship

might be like if they didn’t build this new barn. Could they have chosen to

hold more worship service in their previous, smaller space and given all the

money they’ve spent on new construction and the upkeep of this humongous

facility to the poor? Would they be richer in the things of God if they did? I’m

just asking.

Thanks for visiting, my friends!