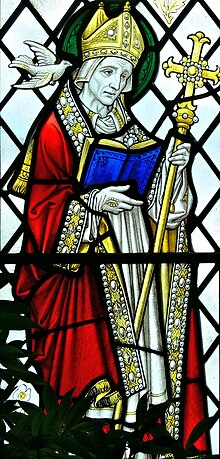

March 1 is the Feast of Saint David,

the patron saint of Wales and the Welsh people. On this Sunday, March

1, 2015, St. David's Lutheran Church of Philadelphia is dedicating a

gorgeous stained glass window depicting the sixth century Celtic

abbot after whom the church was named some sixty-five years ago. I

have to wonder how a Lutheran church—a denomination not

inclined to hagiology and filled with very traditional Americans of

mostly German and Scandinavian roots—could come to name itself

after a fairly obscure ancient Welshman who is patron of a country

roughly the size of New Jersey. Nobody at St. David's Lutheran seems

to know the answer to this.

So I guess it doesn't matter.

I've been asked to be the preacher at

the dedication service, however, because I am of Welsh heritage and

St. David's Day has always been a holiday for me. I'm very proud to

be a Welsh-American. We are a noble, Christian, poetic, musical, and

darn attractive race of people.

(For that last adjective, just check

out Catherine Zeta-Jones and Ioan Gruffudd if you don't believe me.

Oh..! And don't forget Tom Jones and Katherine Jenkins. God may not

have made the Welsh a mighty nation, but He gave us plenty of good

looks!)

But, as usual, I digress.

Before going into the life of St. David

(about which virtually nothing is known with any historical accuracy)

it might be helpful to take a refresher look at the way Lutherans

view the saints. That is, how we view the canonized or otherwise

recognized Christian heroes who have gone before us. In the Augsburg

Confession, Philip Melanchthon wrote:

“...our people teach that the

saints are to be remembered so that we may strengthen our faith when

we see how they experienced grace and how they were helped by faith.”

(CA. XXI)

The

article goes on to explain, however, that Christians need not call

upon the saints for aid as Jesus has already been the true mediator

between God and humanity (see 1 Timothy 2:5). Subsequently, Lutherans

have tended to be a little on the cool side where saints are

concerned. Lutheran churches bearing saints' names tend to choose

such names from the New Testament only, and saints like David get

very little attention.

But, if the stories of the saints

strengthen our faith, I for one would still like to hear them. I

personally think David is a great example for this Second Sunday in

Lent. In our gospel lesson today, Jesus tells his followers,

“If any want to become my

followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and

follow me.” (Mark

8:34b)

The

life of Saint David was certainly filled with a great deal of

self-denial. The legend goes that David's mom, variously known as

Non, Nonna, or Nonita, was a really pious Christian girl living in

the semi-barbaric Wales of the late fifth and early sixth century.

This was just about the time that the Roman Empire was collapsing.

Part of ancient Britain had already embraced Christianity, the

Empire's official religion, but the fledgling faith was facing a

serious threat from invading hordes from which the dwindling Romans

could not protect them. Subsequently, Christian Britain migrated into

the peninsula we call Wales today. This mountainous country provided

a natural defense against the invaders.

Alas

for poor Non, she was raped by a Druid chieftain known as Sant, and

conceived a baby who would become David. Although the chieftain

agreed to take her as his wife, the good girl vowed to remain chaste,

and gave herself over to a life of poverty and good works.

There's

a story that a Christian preacher, approaching the pregnant Non, was

struck mute. He believed this to be a sign that the child she was

bearing would be a greater preacher than he.

The

little boy was destined to a life of service to Christ. He learned to

read by reading the Psalms. He also adopted his mother's love of

poverty and simple living. He became a vegetarian. Later, as an abbot

and founder of monasteries, David insisted his Christian brothers

refrain from the eating of meat or fish. In fact, he was so

respectful of animals that he refused to allow the monks to use oxen

to pull their plows or carts. The brothers were to pull these

vehicles themselves.

All

in all, David spread the Christian faith through the founding of

twelve monasteries. His rule emphasized self-denial and abstinence.

Monks were not allowed to have personal possession, and were

frequently enjoined to periods of silence. In addition to the “no

meat” rule, David's monks also refrained from wine and beer, and

spent weekends without sleep in prayer and contemplation. They were

also instructed to study scripture and to write spiritual works.

Subsequently, David is honored as the patron saint of poets and

vegetarians.

This,

I would think, would be quite enough for one lifetime, but when David

was about sixty years old he was called upon to put out a theological

fire within the church. It seems that some of the Welsh Christians

had adopted the teachings of a heretic named Pelagius. If Pelagius

were around today, I don't doubt he'd have a mega church and his own

TV show since he preached what people love to hear. His basic message

was this: Since we are all made by God, we have a little bit of God's

perfection in us. This gem of God's light enables us to know right

from wrong and evolve to a higher spiritual state. We are all

basically good, but the gospel serves to inspire us to a more Godly

life. Christian Scientists and Scientologists would be nodding in

agreement.

Unfortunately,

Pelagius' doctrine falls flat in the face of obvious evil and selfish

wickedness in this world. We are all created by God, but the

scripture teaches us we all fall short of God's glory.

Some

time around 560 CE, David was called to place called Brefi to address

this false teaching. We don't know what he said on that day, but we

do know that his preaching of the scriptures converted the Pelagians

back to orthodoxy. Perhaps he reminded them of their state of

selfishness, wounded pride, disappointment, envy, and covetousness.

He might have exhorted them to repentance by showing them that, no

matter how they strove to keep God's law, they always fell short and

relapsed back into sin. Maybe he preached to them that they had not

chosen for God to love them, that they had not asked Jesus to take on

human suffering and degradation, that they had not brought about the

miracle of Our Lord's death and resurrection, promising forgiveness

to all by God's grace through sinners' faith. Doubtless he told them

that the road between God and humankind is a one-way street which

goes only from God to us and never the other way around. He might

have comforted them by saying that their salvation had nothing to do

with their own good merits, but only with God's love. They would be

free to be helpless, erring, and contrite. But they would also be

comforted by knowledge that it wasn't all about them. “Deny

yourself,” he might have said, “and take up your cross to follow

Him.”

A

thousand years later, Martin Luther would be preaching the very same

thing.

Legend

says that while David preached, the Holy Spirit rested on him in the

form of a dove on his shoulder, and the ground upon which he stood

rose below his feet to become a small hill. This enabled his voice to

ring through the valley and be heard by all. So powerful was his

preaching that the archbishop of Wales, Dubricius, immediately

relinquished his see and presented his crozier to David.

A

further legend has it that it was David who instructed Christian

Welsh soldiers to wear leeks in their headgear in order to

distinguish themselves from invading pagan Saxons while in the heat

of battle. To this day the leek remains a Welsh national symbol (used

as the collar insignia of Her Majesty's Royal Welsh Guards) although

it's connection to David is probably apocryphal.

Besides

his blow to the Pelagians, David is chiefly remembered for moving the

see of the Welsh church to a spot on the south west coast of the

peninsula which today bears his name and the cathedral dedicated in

his honor. It is a lonely spot where pilgrims can go to shut out the

world and get in touch with their longing for God. We might call it a

“Lenten” spot.

So.

Thinking of David on this Second Sunday of Lent, let's not put our

minds on the things we want,

since all we can do is cater to our own selfishness. Let's do the

“little things” (as David would say) of praying, fasting, finding

quiet time, and contemplating all that God does for us.

God

bless.