|

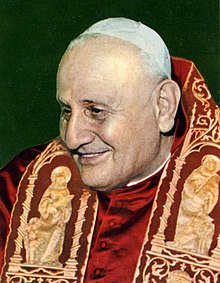

| Shimon Peres (center) with fellow Nobel laureates Arafat and Rabin |

“And if the same person sins against you

seven times a day, and turns back to you seven times and says, ‘I repent,’ you

must forgive.” (Luke 17:4)

Israeli politician Shimon Peres went home

to meet the Lord this week, and a

really big fuss was made over his passing. That’s only fitting as the guy had a

career which spanned over sixty years in public life, held the record for being

the oldest codger (over ninety-years-old!!) to be a head of state, and won the

Nobel Peace Prize in 1994.

I think of Peres as I meditate on the Gospel

lesson the Revised Common Lectionary for Pentecost Twenty, Year C (Luke

17:5-10). In order to understand this snippet of scripture, however, I think we

have to look at the verses which come before it. In Luke 17:1-4, Jesus is

telling his followers not to screw things up. Of course we’re all going to make

mistakes—say things we wish we hadn’t said and do things we wish we hadn’t done

and generally be our usual stupid, sinful selves. Nevertheless, Jesus is

telling us to look sharp lest our hypocrisy damages the faith of others.

Chiefly, he’s warning us against intolerance and lack of forgiveness.

It’s that last part—forgiveness—which makes

me think of the late Israeli Prime Minister. If ever there was a dude who tried

to get along with people who hated his guts, it was Shimon Peres. Not only

could he get one of his arch political rivals, Yitzhak Rabin, on his side, but he

even managed to get an agreement with PLO leader Yasser Arafat, too. I mean, it’s

no big secret the Israelis and Palestinians don’t exactly slow dance with each

other. After decades of violence, hatred, and mutual suspicion, Peres snuck

behind his nation’s back and made the daring move to talk to his enemies. These talks eventually led to the Oslo Peace

Accords and the Nobel Peace Prize for Peres, Rabin, and Arafat.

Alas, the peace process hasn’t gone

particularly smoothly since the accords were signed in 1994. Even after things

went south between the Israelis and Palestinians, Peres continued to push for

peace and reconciliation. For me, his persistence embodies Jesus’ command to

forgive “seventy times seven (Mathew 18:22).” For a Jew, he made a better

Christian than some Christians.

Of course, there are those who believe

there will never be peace between the

factions in the Holy Land. Forgiveness, peace, and understanding require faith.

It’s no wonder that the followers of Jesus in Luke 17 ask to have their faith

increased after Jesus admonishes them about the need for forgiveness. But Jesus

isn’t listening to excuses. He doesn’t have time for his divine teaching to be

answered with some lame balderdash like, “I really wish I could make peace with

that person, but I just don’t believe it’s going to happen. They just don’t

listen to me or respect me. I guess I don’t have enough faith in them or myself

to even try.”

Jesus’ response to this could be summed up

as: “What a load of crap! If you had the faith of a mustard seed—and, grammatically

speaking, you DO—then you could accomplish miracles. I didn’t give you a

command knowing that you couldn’t

keep it. I told you what I expect of you. I expect both repentance and forgiveness, and you have faith

enough for that already.”

Repentance and forgiveness are minimum

requirements. It’s nice to get a Nobel Peace Prize, but reconciliation is what

were supposed to be about. My hat is

off to folks like Shimon Peres, Lutheran World Federation President Munib

Younan, Jimmy Carter, Karen Armstrong, and all of the saints who have faith

enough to believe that peace, empathy, and harmonious interaction between

diverse peoples are right and achievable goals. Violence, force, intimidation,

and animosity only beget themselves. Resentment and un-forgiveness, as the old

saying goes, are like drinking poison yourself and hoping it will make your

enemy die.

Shalom to you, Mr.

Peres. You tried to do what God expects of all of us. I’m glad you got the

Nobel Prize, but I hope you know you did only what you ought to have done.

God be with you, my friends.