“…and the disgrace of his people he will

take away from all the earth.” (Isaiah

25:8b)

And so we go on.

The seasons change. The autumn comes as it

must every year. The days get shorter and darker and colder. The leaves give

one last explosive burst of color before shriveling and falling dead to the

earth. And we, in both thanksgiving and dismay, recall the dead. All the saints

who have gone before us whom we miss and mourn and will continue to love.

During the masses held on Sunday, November

4, 2018, the candles will again be placed on the altar and lit as the names of

the dead are read. They will be the names of ordinary people. No generals or

statesmen or rock stars. Just good folks who left their marks on the hearts of

my parishioners. Just those whose lives were, in their way, every bit as epic

as the lives of any hero out of mythology. They were people who knew all the

joy and love and pain and disappointment of being a human being. Each one a

sinner. Each one a saint redeemed by the blood of Jesus.

One name we’ll read will be that of John

Bridel, a gentle, quiet, honest man in his late 80’s. He served his country in

Korea, his family by being a hard-working husband and father, and his church in

myriad ways. A man of extraordinary generosity and soft-spoken piety, John had

served on the committee which called me to this parish almost twenty years ago.

I visited him and his wife, Mary, frequently in his last years when orthopedic

ailments confined him to his home. Often he’d tell me stories of his childhood

in Philly in the 1930’s and ‘40’s—tales of orange crates turned into scooters

and games of “half ball” in the streets—things I’d only heard of or seen in old

Our Gang comedies.

John was a devout Lutheran. Mary is a

devout Roman Catholic. For over sixty years they’d go their separate ways every

Sunday morning and come together again for Sunday dinner, living out the words

of St. Peter: “I truly understand that God shows no partiality, but in every

nation anyone who fears him and does what is right is acceptable to him” (Acts

10:34)

Another candle to be lit will be for Edna

Guenther, a sweet, roly-poly, motherly little lady who, from her wheelchair,

made sure she always had cheese and crackers or a meatball sandwich ready when

her pastor came to visit. We called her “Miss Edna” as had the dozens and

dozens of Sunday School children she’d taught over the decades—some of whom

teach in our Sunday School today. Loving and sentimental, Miss Edna might start

to cry if you sang one of the old Sunday School songs to her like “This Little

Light of Mine” or “Jesus Loves Me.” All she ever wanted to do was tell little

children about Jesus, and doing so gave her so much joy.

We will light a candle for Richie

Steinmuller, who passed away suddenly last year of a brain aneurysm. He was in

his mid 30’s. Richie may have made some mistakes in his youth, but he more than

made up for them as a good son, an encouraging friend, a hard and ambitious

worker, and an awesome dad to his two children. His life, however brief, was a

testimony to the redemptive healing power of God.

I’ll also call out the name of Barb

Edwards, who, though not a member of the parish, always worshiped with us when

she came down from Allentown to see her daughter, Caroline. Cheerful in spite

of physical ailments, Barb was a perpetual volunteer with her daughter at our

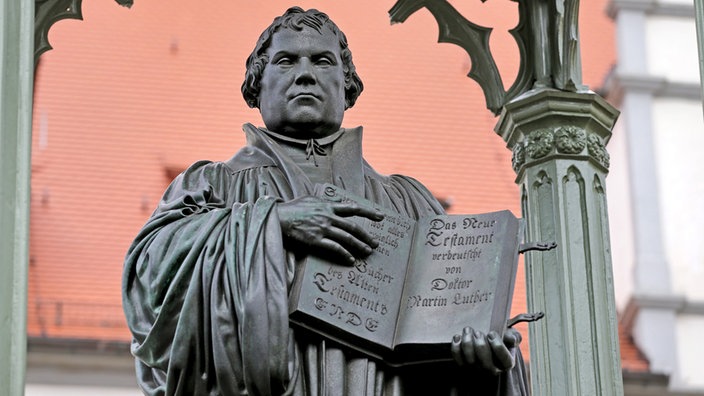

church’s annual Fall Festival. She demonstrated Luther’s concept of the

Priesthood of All Believers through her career with the Pennsylvania State

Board of Probation and Parole, and her constant volunteering with such organizations as Meals

on Wheels and Sacred Heart Hospital of Allentown.

After Barb passed, Caroline shared a revealing

anecdote about her mother. Barb’s husband of over forty years, Clyde, died on a

Saturday. Barb was in church the following Sunday morning. I find this

significant as I’ve so often seen people drift away from the church when a

loved one dies. They so closely associate the worship of God with their departed

family member that they can’t sit in God’s house without wanting to cry. Barb

understood that God’s house was the best

place in which to cry. She had a sense of religious discipline. "Remember the Sabbath day, and keep it holy." When young

people tell me they are “spiritual but not religious,” I honestly find that to

be absurd. Spirituality grows out of discipline. One could be religious without

ever being spiritual, but I doubt anyone can be spiritual without first being

religious. Barb was both.

I thank God for the witness of the saints

I have mentioned above, but I would be remiss this All Saints Day if I did not

also grieve for the martyrs. Let’s not forget the youngsters killed on Valentine’s

Day at Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland Florida. Let’s say a

prayer for the families of Maurice Stallard and Vicki Lee Jones, two African

Americans who were gunned down in Louisville on October 22nd simply

because of the color of their skin. Let us mourn with the congregation of Tree

of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh as they mourn for the eleven dead—murdered in

their own house of worship simply because of their religion.

Personally, I will mourn for Alyssa

McCloskey and Colleen Brownell, two step-sisters who loved each other every bit

as much as blood siblings do. They were both murdered in Alyssa’s home last

December, knifed to death by a sick, narcissistic former boyfriend of Colleen’s.

Between them they left behind three sons and two caring parents, Richard and

Sandra, to whom I could offer no comfort except to say that the manner of their

girls’ death must not define their lives.

This is a time to mourn. We mourn for

those whose passing was merely sad and those whose passing was deeply tragic.

We mourn for a nation and a world where acts of violence are still so common.

But we remember, too, that we serve a God who saw his own son die a violent

death, a God who mourns with us, and a God who promises one to day wipe the

tears from our eyes and remove the disgrace of our sin forever.

And so—in this faith—we go on.