|

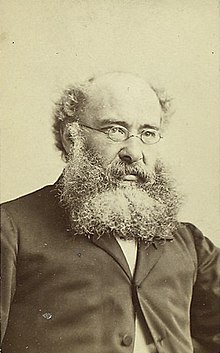

| Anthony Trollope |

I really love Victorian British

literature. It’s sort of a hobby of mine. It’s all in public domain now, so I

can download it for free on my Amazon

Kindle and relax from the cares of parish ministry by retreating into a

world where manners were everything, English prose were mellifluous, Victoria

sat enthroned in Britannic glory, and Donald Trump did not exist at all.

Of course, the great paragon of this

period of English letters was Charles Dickens, and I have read through most of

his canon with delight and relish at his quixotic and unforgettable characterizations

and brilliantly convoluted diction. But Dickens wasn’t the only grand voice of

Good Queen Vicky’s reign. I’d like to take the opportunity to celebrate two

other gentlemen who also speak to my sense of lyrical whimsy.

We all should know Lewis Carroll as the

author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

and Through the Looking Glass. These

two wonderful volumes have amused children of all ages for over a century. They

are delightfully whacky and nonsensical. What you may not know, however, is

that Lewis Carroll—whose real name was Charles Dodgson (1832-1898)—was, in

addition to being a mathematics lecturer at Oxford University, an ordained

deacon of the Church of England.

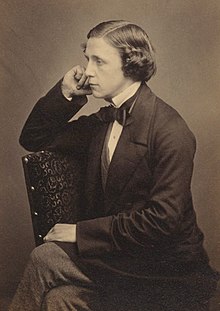

|

| Lewis Carroll |

I’m including the Reverend Mr. Dodgson in my

hagiology because, after reading a biography of this deeply spiritual man, I

found him to be remarkably liberal in his thinking and, actually, quite ahead of

his time. I’ll site only one example:

As a man of letters, Dodgson was naturally

very fond of Shakespeare. He was also a great, if platonic, friend of the

famous actress Ellen Terry. In a letter to Terry he shared a thought after

having attended a performance of The

Merchant of Venice. Although he always enjoyed the play, Dodgson was deeply

disturbed by the ending in which the Jew Shylock, after losing his court case,

is forced to be baptized as a Christian. Dodgson expressed that he felt forcing

the Jew to abandon his faith was unreasonably cruel and marred Shakespeare’s

otherwise happy ending. He suggested to Terry that the line about Shylock’s

forced conversion be cut from future productions. This seems to me to be

extremely enlightened and ecumenical in a man of the 19th Century.

It speaks to Dodgson’s sense of compassion. As a cleric who is now dealing with

interfaith issues, I have to applaud Deacon Dodgson for expressing a thought

which might have been distasteful and controversial to other churchmen of his

day.

My other champion of Victorian literati is

the far-less-known Anthony Trollope (1815-1882). I doubt students are ever forced

to read Trollope in American high schools, and I guess his effect on English

letters is far less substantial than that of Dickens, Hardy, Elliot, or even

Lewis Carroll. But Trollope certainly speaks to me.

Why? Because he painted so may clerical portraits

in his novels. Many of his characters are Church of England priests, and I have

to say he really seems to get it. (It

also surprised me how little has changed for pastors in over 100 years!) In The Vicar of Bullhampton, a country

parson attempts to rescue a “fallen woman” in his flock, and wonders if he’d

care so much about her if she weren’t young and pretty. In a collection called The Barsetshire Chronicles, Trollope

paints convincing pictures of a henpecked bishop, a conniving chaplain, a morally

conflicted cantor, an archdeacon obsessed with maintaining respect, and a young,

single priest pursued by an amorous parishioner. All of these characters seem

very real to me, and I found comfort in Trollope’s attempt to characterize his

clerics as three-dimensional human beings. After all, pastors are people too.

What most qualifies Trollope for sainthood

in my book, however, is the characterization of women. Whereas Dicken’s women

are either virginal paragons of demure virtue, frightful harpies, or eccentric

crones, Trollope’s ladies are often witty and realistically vulnerable. His

heroine’s aren’t always pretty, and they are frequently complex. Rachel O’Mahoney

of The Landleaguers is feisty and

downright acerbic and has many of the more humorous lines in the novel. Miss

Dunstable, the homely but massively wealthy heiress in Doctor Thorne and Framley Parsonage is at once comic, wise, and truly touching.

Trollope also takes aim at British class

culture. For a man who seems to deeply love the institutions of his native land

and time, he has quite democratic tendencies, and often takes sly aim at people

in high places. Quite naturally, he writes with the strong moral views of his

age, but I don’t think these views are in anyway amiss today.

Should you get the chance, read a little Trollope. You might enjoy him. Or re-read Alice in Wonderland. It will do your heart good.

No comments:

Post a Comment