Maundy

Thursday is a rather contradictory festival.

First off, I guess, because we can’t seem to agree what to call it. Sometimes

we say “Maundy Thursday” and sometimes we call it “Holy Thursday.” The confusion

is doubtless because most folks don’t know what the heck “Maundy” means. In

case you’re in doubt yourself, let me explain that “Maundy” comes from a Latin

root meaning “mandate” or “command.” On this occasion Christians remember two things

Jesus was insistent that we do:

“Love

one another as I have loved you.” (John 13:34) and

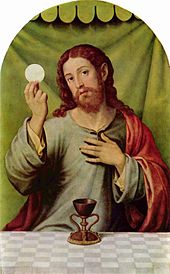

“Do

this in remembrance of me.” (Luke 22:19 and 1 Corinthians 11:24).

We

usually marry that first command to the ritual of washing feet. In John’s

gospel (John 13:1-17) Jesus takes the slave’s job of washing his disciples

dirty, stinky feet—an act of humility indicating an end to arrogance and rank

distinction and a call to love others in charity and dignity. The second

command is an order to keep Christ’s sacrifice alive by gathering together for

a common meal.

I’m

always up for a good dinner party. In fact, I can’t think of many things more

enjoyable than sharing a meal with people I love. But this particular meal is fraught

with contradictions. It’s supposed to be a festival meal—a party—right? But it

is also a reminder of a pretty unpleasant night in Jesus’ life. So what’s up

with that?

Jesus

and his buddies are celebrating—that’s the right word for it—the Passover. They

were remembering something really cool that God did for their people. God led

their ancestors out of the bondage of slavery in Egypt and through the parting

waters of the Red Sea because God does not desire oppression, cruelty, or

bondage for anyone. But there was a catch: God made a covenant with the people

at Mount Sinai. Because God was so good, the people were ordered to love God

and love everyone else from that time on—an order they (and we) can never seem

to obey.

So,

on that Passover night which we remember this Thursday, God in Jesus made a new

covenant. “Do this,” Jesus said, “in

remembrance of me.” Before that night, you see, the people were in the habit of

going to the temple and offering up ritual sacrifices in order to pay off God

for their failure to keep God’s command of love. This was a pretty elaborate

ritual, and one from which many—possibly Jesus himself because of his

questionable parentage—were excluded. So Jesus gave us a new ritual from which

no one would be excluded. No longer would people need to bring animal flesh to

burn on the temple altar or splash blood on the altar’s blistering hot sides.

In fact, they would never again have to offer sacrifice for atonement for the

failures of being human. Instead, we were to gather together to eat the bread

and drink the wine of the Passover, the festival of freedom, and remember that

Jesus had freed us by sacrificing himself.

But that night when Jesus celebrated with his friends ended with his being betrayed, arrested, abandoned, mocked, beaten, and sentenced to death, making this dinner party both joyful and sorrowful.

But that night when Jesus celebrated with his friends ended with his being betrayed, arrested, abandoned, mocked, beaten, and sentenced to death, making this dinner party both joyful and sorrowful.

When

we take the bread we recall his body was broken. In the wine we remember his

blood was spilled. We celebrate by remembering how, on that awful night, Jesus

took on everything we endure or fear.

When

we eat the meal, Jesus is here with us, physically. He is with us when we are

anxious, just as he and his disciples must have been anxious and full of foreboding

on that night so long ago. He is with us when we are wounded by a loved one. He

is with us when we are disappointed by those whom we have trusted. He is with

us when we feel abandoned. He is with us when we are accused and blamed and

bullied and made to feel helpless and worthless. He is with us when we are held

captive to anything toxic in our lives. He is with us when we are grieving. He

is with us when our bodies, ache, bleed, and fail. He is with us when we face

death. For he endured all of these things on that night.

So

we eat this meal and recall that God is with us, and we are with God. We are

known. We are family. We are forgiven. In all of our frailty and weakness and

regret, God is with us and in us.

Such

things, such unity and wholeness are not true because the act of eating and

drinking is some magic ritual. They are not so because the celebrant is so holy

that he or she can turn bread and wine into flesh and blood. Rather,

forgiveness, life, and salvation come simply because Jesus promised us they

would, and we believe his promise.

And

because we believe, we are transformed.

No comments:

Post a Comment