“You always have the poor with you, but

you do not always have me.” (John 12:8)

I’ll be the first to admit that the Bible can be frustrating at times. Take the gospel reading for Lent 4, Year C (John 12:1-8). It’s the story of Jesus getting anointed with expensive fragrance by Mary of Bethany when he comes to dinner with her and her siblings. Judas Iscariot looks askance at this anointing because Mary is spilling some really expensive product on the Lord’s feet. Judas thinks the cash she’s shelled out for this high-end stuff might be put to better use in feeding starving people.

Frustrating? Yup. For two reasons. First, Judas—that arch “bad guy”—is actually making a pretty valid point. It’s kind of like the way I would feel if Donald Trump ever said anything intelligent. Some people you just hate to side with! But one of the really frustrating things we encounter in scripture is the inability of the gospel writers to get their story straight. The anointing of Jesus with costly fragrance appears in all four gospels, but the details morph with each gospel writer. What the evangelists all agree on is that some chick anointed Jesus shortly before his crucifixion, she spent a boatload of cash on the ointment, and some onlookers gave her a hard time because this act was so extravagant and—to their pea-brained minds—wasteful. We don’t know—and it’s not really important—what actually happened. Stories were told and re-told in the ancient world, and each teller put his own spin on them according to the audience he was speaking to or the point he wanted to make. Matthew and Mark say the anointing was done by “a woman,” but they don’t identify her even though, ironically, Jesus comments that she will always be remembered. Luke says the perfume lady was “a woman of the city, who was a sinner,” presumably a prostitute.[i] In our version from the gospel of John, the woman is identified as Mary of Bethany.

These divergences can mess you up if you’re hung up on accuracy, so I’d advise taking each story on its own face value. Personally, I like the Luke and John versions of the story because these guys give the woman a good reason for doing what she’s doing—which, in the world of the text, is a pretty outlandish thing. If, as in Luke’s version, you’re just a skank ho and everybody looks down on you, you’d likely be pretty darn thankful that the rabbi from Nazareth saw you as a human being and forgave you your sins. If you’re Mary of Bethany, you might have an even better reason to be uber grateful to Jesus.

In John 11 we have the story of the raising of Lazarus, the brother of Mary and her sister Martha. Because John mentions that Martha was serving at table when Jesus came to dinner (v.2), I’m guessing this family wasn’t wealthy enough to afford a servant. They were probably pretty middle class folks, just trying to get by. The sisters are living with their brother, which says to me that they were unmarried. Unattached ladies, in this patriarchal world, were kind of dependent on the men in their families to get along. Lazarus’ death meant that his sisters would be out their source of support. They’d have to beg or find other relatives or marry someone they didn’t like just to have a roof over their heads. Additionally, as they bawled their eyes out at the funeral in chapter 11, they probably really loved their brother and were devastated when he died.

I always say the worst loss we can suffer is the loss of our own children. Our kids are supposed to bury us, not the other way around. But when we hit a certain age, the loss of a brother or sister can really tear us apart. Think about it: is there anyone in your life who really knows you like the ones who grew up under the same roof you did? Your siblings know all the skeletons in all the closets. They know your high school nickname and all about your first crush and the dumb thing you did when you were ten. Unless you have a childhood pal you’re still close with, there’s nobody in your life who knows your story like your sibling does. Not your spouse and certainly not your kids. When a sibling dies, a piece of your story dies too.

If you’re Mary of Bethany, how joyful and thankful would you be to get your dead brother back alive again? How could you ever repay the guy who shouted, “Lazarus, come out!” and gave you back your brother, your friend, and your protector? You really can’t blame Mary for wanting to show her appreciation to Jesus. Her joy must’ve been ineffable, beyond words. So? If words won’t do, she makes a gesture. It was customary to greet visitors to your home by anointing their sunburned heads or washing their dirty feet. Mary not only anoints Jesus’ feet but dries them with her hair. It’s her expression of devotion and extreme gratitude. When have you ever felt that sense of thankfulness and devotion? When a thank-you card isn’t enough, you may have wanted to make a more substantial gesture.

Lent is a good time to reflect on just how good God has been to each of us. If you’ve ever experienced rescue, relief, or any surpassing blessing—especially at a time when you thought you were really going to be screwed—a gesture of thanks might be in order. Jesus defends Mary’s expensive[ii] outpouring of love because he knows it comes from her heart. It also comes at just the right moment. There’s been some nasty talk about Jesus at the end of chapter 11 (vv.45-57), and it’s possible he might be in some real trouble. By 12:20, when some foreign guys[iii] come looking for Jesus, he knows he’s famous enough to be on the Pharisees’ hit list.

Expensive scented oil could’ve been used as part of the burial rites of the day. Folks would anoint a swaddled corpse with this stuff to disguise the stench of rotting flesh until there was nothing left but bones which would be placed in a box called an ossuary. Of course, by the time they poured the perfume on you, you were in no position to appreciate the smell. Mary doesn’t lose any time and doesn’t want to regret not having expressed her love to Jesus in person.

The poor will always be with us, year in and year out, and it’s always our duty to love, assist, and uplift them. But gratitude is also always in season, and it’s not a bad idea to express it to God and to others while there’s still time.

[i] In

the 6th century Pope Gregory I preached a sermon in which he

identified this floozy as Mary Magdalene, even though no straight reading of Luke’s

gospel would make you think the two women were one and the same. The pope

managed to ruin poor Mary’s reputation for centuries to come!

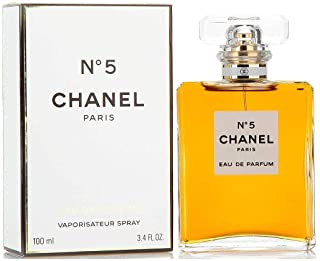

[ii] BTW,

have you tried buying perfume (or parfum

as the fancy stores call it) lately? The price of the jug of nard Mary used would

run over $11 grand at today’s prices! Nard came from the valerian plant so it

had to be imported. That’s what made it so expensive. Its pleasing aroma was

often used in the ancient Hellenistic world as a sleep aid. It’s still used

today.

[iii]

They’re referred to as “some Greeks.” This basically meant they weren’t Jewish.

They could’ve come from anywhere as the universal language at that time was

Greek and whatever your native tongue was, you could get along if you also

spoke Greek.