“…whoever wishes to become great among you must be a

slave of all.” (Mark 10:43)

Oh, those whacky Zebedee boys! They’re at

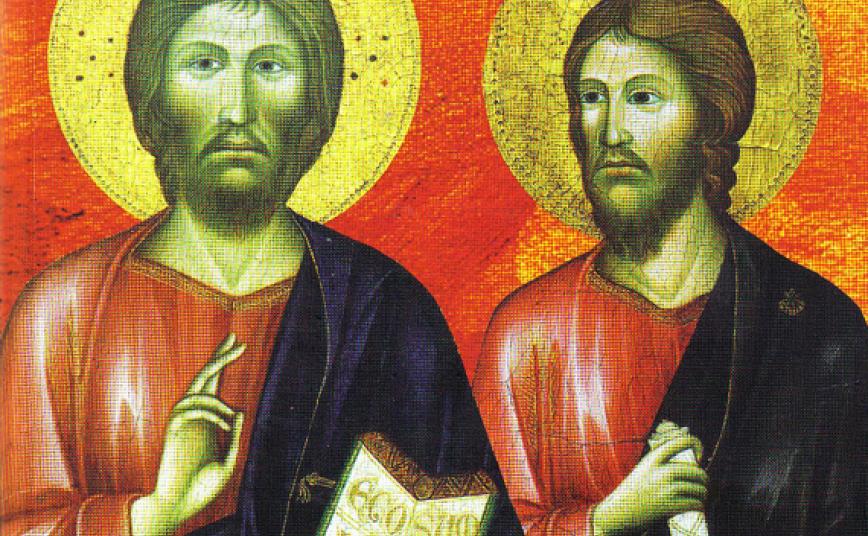

it again. In the Gospel appointed for Pentecost 22, Year B (Mark 10:35-45),

James and John get a little giddy at the prospect of approaching Jerusalem.

They just can’t wait to enter the city and see Jesus hailed as the Messiah.

But, boy..! Do they have a surprise coming!

If you’ve been reading along in Mark’s

Gospel, you might’ve noticed that Jesus has told the disciples no less than three times[i]

that he’s going to be rejected and crucified. Nevertheless, it seems to have

gone in one ear and out the other for these two lads. They can’t wait to see

the crowds mobilize, hail Jesus as king, and take important seats in his new

government. They want to sit at the right and left hand—Vice President and

Secretary of State. Yup! They’re going to throw out that slimy bunch of pagan

Romans and their Sadducee myrmidons and take over the whole operation

themselves. They’ll show those foreign scumbags that they’ve messed with the

wrong bunch of Chosen People.

So Jesus has to bring them up short and

ask them if they’re willing to suffer the same way he’s willing to suffer.

Naturally, they tell him they’ll endure anything for the sake of the prize which

is at stake. Then Jesus has to tell them that their suffering is pretty much

guaranteed—but the prize isn’t. If they want to know what greatness is, they

have to become slaves.

They must’ve thought that sucked. After

all, what good is greatness if you’re not GREATER than somebody else?

That’s one of the problems with this text.

It’s so easy to make our suffering and our serving a competition. It’s easy to

criticize James and John for their ambition, but it’s harder to criticize

ourselves for our glorious humility. It’s also hard to tell the difference at

times between actually serving and

just being a doormat for someone. There’s a thin line between a sacrifice and

an out-and-out waste. What if what we think is humble service to the Lord is

actually enabling someone else’s bad behavior?

Oh! And what about those poor, afflicted

souls who have every right to be miserable, depressed and cranky—and actually

choose to exercise that right? You

know who I’m talking about. It’s the ones who can’t believe that anyone’s

suffering could be greater than theirs. They use their weakness to lord it over

others just as the “gentiles” Jesus refers to in our lesson use their power and

position.

How do we come to terms with our sense of

wounded entitlement? I recently read W. Somerset Maugham’s 1906 comic novel The Bishop’s Apron, and I had one of

those dark epiphanies which I find so uncomfortable. The main character in the

book is an Anglican pastor named Theodore Spratte who desperately wants to

become a bishop. Spratte feels he’s entitled to wear the gators and apron of

the episcopal post. He’s witty, charming, eloquent, and the son of a prominent

peer. He’s put in twenty years of service with his London congregation, and he

feels he’s earned a promotion. When a bishopric opens up he feels certain he

will be named. Unfortunately for him, he is only offered a minor deanery in

Wales.

For a brief moment, Spratte grasps his own

unimportance and begins to see himself the way others might see him—overly

ambitious, vain, pretentious, and foolish. His ego cracks, and he has the

opportunity to embrace a real humility. He considers the honor it might be to

serve the Church away from the limelight and do good works for their own sake

without the glory he has so coveted.

Of course, Maugham’s novel is a comedy, so

Spratte doesn’t waste too much time on acquiring self-knowledge before talking

himself back into his old self-satisfied grandiosity. When I read this, I

confess I squirmed a bit in my easy chair. Coming to terms with my own

brokenness is just a little too uncomfortable for me—just as it might be for

you, too.

But Jesus doesn’t pull any punches here.

He tells us quite plainly that we will drink the cup of sorrow and be washed in

the bath of suffering. It’s a fact, but it’s never a competition. Lowliness,

loneliness, suffering, hurt, disappointment, and pain aren’t meant to make us

better than others. They can best serve to unite

us with others. Jesus chose this path in order to be united with us.

There’s really no point in looking for a

reward on this side of eternity, is there? If you think by living a good and

virtuous life God will reward you with good and virtuous things, that’s not

really religion. It’s superstition. We can’t influence God. Religion—real faith—is

letting God influence us.[ii]

Thanks for stopping by. Please come again!

No comments:

Post a Comment