So they went out and fled from the tomb,

for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for

they were afraid.” (Mark 16:8)

So they went out and fled from the tomb,

for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for

they were afraid.” (Mark 16:8)

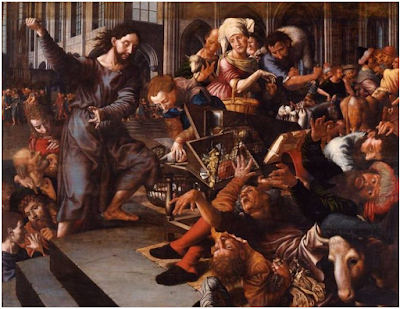

It’s not hard to relate to the ladies who went to Jesus’ tomb on that first Easter, is it? I mean, once you’ve watched someone die a horrific death, it’s going to be pretty hard to believe they’ve come back to life—even if some guy who looks for all the world like an angel is telling you that this is the case. Mark tells us that these women were sized with “terror and amazement” when they found the tomb empty and got this piece of news.

As always, and in the spirit of academic geekiness, I had to look up “terror and amazement” in my Greek Bible. The words Mark actually uses are tromos (tromos in Greek spelling)[i] and ek-stasis (ek-stasis) which literally translate as “trembling” and “bewilderment.” Ek-stasis, however, can also imply a trance-like state, a state in which your senses freeze you to the spot. Now Mark just told us that the women weren’t frozen. In fact, they couldn’t get out of that tomb fast enough! I don’t think they were afraid for their lives, I just think they were afraid the news was too good to be true. News that good had to be emotionally paralyzing. What if they’d just hallucinated it? After all, how can life come from a bloody and degrading crucifixion? It probably didn’t make any kind of sense to them. Better say nothing until they figured it out.

But if we know nothing else about God, it’s that we really know nothing about God. God just keeps surprising us with stuff we never expected. God loves to keep us trembling and bewildered.

One of God’s best promises—one that is always counterintuitive to our puny way of thinking—is that whenever things look their crappiest, something jaw-dropping may be about to happen.

A few weeks back I heard an amazing story on NPR’s On Being[ii] series. Rabbi Ariel Burger told a story illustrating the message of Easter—how God takes on our wounds and gives us life in return. It seems that Burger’s son had a friend named Mason who was visiting historic Jewish sites in Poland. Mason disappeared for a day to make a visit to an elderly gent outside of Warsaw, and, upon his return, told young Burger the purpose of his visit.

Mason’s Polish grandparents had been married just three weeks before the Nazis had them deported to Auschwitz. Every night Mason’s grandfather would go to the fence which separated the men’s side of the camp from the women’s and see his bride. He’d often bring her an extra piece of bread or a potato or anything he could save or smuggle.

Unfortunately, the young bride was soon transferred to work on a rabbit farm outside of the camp. The Germans were using rabbits to experiment on so they could find a cure for typhus. The Polish gentile who ran the farm noticed that the Nazis fed and cared for the rabbits better than they cared for their Jewish slave laborers, so he began to sneak food to the prisoners.

One day Mason’s grandmother cut her arm on a piece of barbed wire. The cut became infected, and the Nazis had no intention to sacrifice antibiotics on a Jewish slave laborer. Realizing that this could be a fatal wound, the rabbit farmer cut his own arm and placed his wound on that of the young woman, thereby infecting himself. He told the Nazi doctors that he was one of their best mangers and, should he die from his infection, the Nazis’ research project would suffer. The Germans gave him the antibiotics which he shared with the young prisoner. He took her wound upon himself and, in so doing, saved her. Six decades later her grandson would track down this selfless man and tell him, “Thank you for my life.”

This story is a metaphor for our Easter salvation. Christ shared our wounds and gave us his life—eternal life. So today we gather to say, “Thank you for my life!” The miracle of our faith is not that a human being was like God, but that God was willing to become so human for our sake.

Today we rejoice that God in Christ transforms our longing into hope because God in Christ brings life out of death. Even a pandemic can mean a transformation into something new and unexpected, the reality of which we are yet to understand. Like the women at the tomb we may fear good news and stand trembling and bewildered today, but God’s Good News will always find a way.

Christ has died, but Christ is risen. He is risen indeed. Alleluia!

[i] You

don’t need to know that. I just think it makes me look smart when I write it in

Greek.

[ii]

Of course, Rabbi Burger wasn’t intending to preach the Christian Easter story,

good Jewish scholar that he is. Still, I don’t think he’d mind a Lutheran

Christian appropriating this tale. It’s a good tale and can enlighten anyone.

If you want to hear him tell it, you can click on the link here: Rabbi Burger.